I often catch myself thinking: ”None of this is real.”

It becomes a mantra. A heuristic of sorts. I’m in my second phase of culture shock; having gotten used to much of Arabic society, I must now learn to appreciate this uncanny familiarity. I’ve been living in Morocco now for over a month, after living abroad in several countries with THINK Global School. Traveling has become so familiar to me that it’s unfamiliar. I shouldn’t get used to such a nomadic lifestyle, I know, but it’s too late.

My body is angry at me. As I lounge on the bed of of my hotel room, it is tired and restless. The crook of my neck aches from having awkwardly slept on a bus. My legs are covered in bruises – got kicked accidentally in the marketplace here, or fell down millenium-old steps there. Red skin on my feet reminds me of one too many paved streets. Wait, is that scar on my knee from Perú?

My French is odd and clunky in my mouth, like fitting into a curvy friend’s clothes. It’s the Moroccan accent clouding over mine. My English is filled with slang, abbreviations, and grammatical errors. Rusty. On the other hand, my mouth is still negotiating with Arabic to manage its rolls, clucks, and turns of the tongue. Best to simply rely on Salam and Choukra for now, I resign myself.

One of my hands is blue, smeared with directions on how to navigate the Medina, the old part of town. It’s a kind of labyrinth common to each Moroccan city, in which donkeys and motorcycles awkwardly share alleyways. Floral patterns swirl around my other hand where a stranger experimented with henna. The recipe spins in my mind like a chant: eucalyptus paste, lemon juice, and sugar.

My mind is like this room, this hotel room that I call mine.

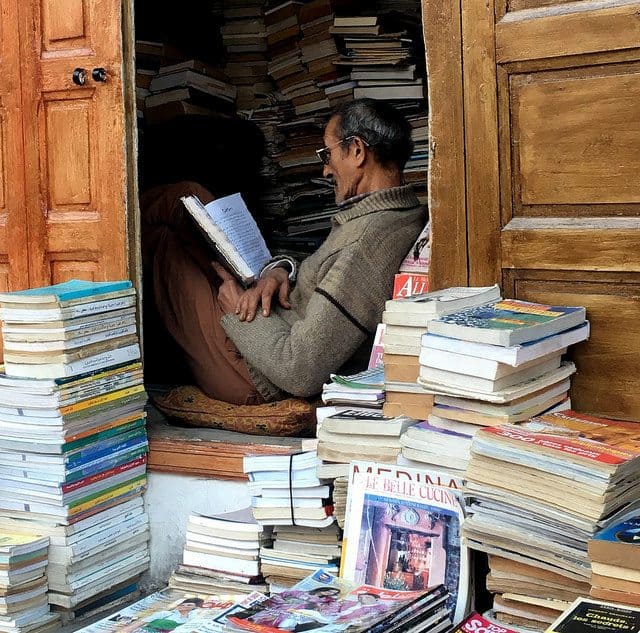

At my right hangs a painting, one of those chic modern ones, covered in memorabilia from home. The color of the smiling faces, ribbons, and stickers seems to be the only tangible thing in the room. In front of me there are nine books, four of which come from different countries. These stories have carved me up, and I can’t let go, even if that means hauling them through the airport as carry-ons.

The crispy pages of one of them reminds me of an afternoon spent running through the sticky hot rain of Rabat. Another’s battered cover brings back the memory of an evening spent searching for the best street food in Marrakech. I can still hear the purrs and pleas of its vendors: ”Gazelle, come back!”, and ”Beautiful, only the best here. Half price for you!”

In front of the novels lays a mug of Earl Grey, cold, forgotten, acrid. I’ve never come to like the traditional glass of Moroccan mint tea, even after having so many hospitable locals offer it to me in greeting. You see, just as I won’t forget how kind these people are to foreigners, I’ll forever be wary of the sickly sweetness of their drinks.

Around the cup sits a packet of vitamins, and beside it, sealed letters with no addressee. I should probably send those soon. Maybe. ”They miss you’,’ a voice murmurs in my head. I ignore it.

There’s vinegar for everyday use in cleaning. It’s become one of my biggest traveling tricks. What more? A lone battery. A box of expensive Belgian chocolates. An air freshener that vaguely smells of home. Permanent markers to satisfy my roommate’s urge to draw intricate designs on her skin. A sock with holes on the big toe. Perfumed scarves I wore in Fès, wrapped around my head and face to cover the stench of the traditional tanneries. Hand wraps I’ve been using for my kickboxing classes. ‘‘Next time, I’ll be able to defend myself,’’ the voice says. For now, the bandages hang in my bathroom and act as cheap laundry lines. On the floor are some notebooks I hurriedly scribbled in on an overnight train.

My mind is like this room – a mess of miscellaneous objects and intangible things. This room is full of stories, of sights, and sounds, and smells. This room is the sum of my life, of my experiences with the school.

Outside, there are car honks, and shouts, and plates clattering at the men’s café next door, and music, and flags slapping in the wind. Rabat is drowning in festivities; proud men just won a football game.

The country is pressing in.

I’m in Morocco, and it’s beautiful, and it’s absurd how dependent I’ve become to this place, to traveling.

”None of this is real,” I whisper.

And yet the pang I feel in my chest is out of pure bliss.